Name a genius.

Einstein, Leonardo Da Vinci, or Mozart may be some of the names that popped in your head, but you probably didn’t think of any woman. Why?

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, women were blamed for having too much passion, imagination, and sexual appetite. By the late eighteen century, however, these qualities had been valued and appropriate for male artists. As new and old concepts of woman and genius clashed, there evolved a rhetoric of sexual apartheid which today still affects our perceptions of cultural achievement. (Battersby, 1990)

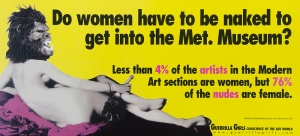

The term “genius” and its trappings (the brilliant, the sublime etc.) in the past have been exclusively bestowed onto men, narrowing the definition of whose cultural contribution is worthy. The lack of women and minorities in the art and culture scene is a social issue that has been addressed by numerous contemporary artist, such as the Guerrilla Girls.

Guerrilla Girls are an anonymous group of feminist artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world. They formed in New York City in 1985, with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality in the fine arts into focus within the greater community.

They use facts, humour and outrageous visuals to expose gender and ethnic bias as well as corruption in politics, art, film, and pop culture. They believe in an intersectional feminism that fights discrimination and supports human rights for all people and all genders. I listened to some of their interviews, and I found myself agreeing with them on many topics.

Some people argue that the representation of all genders in art is not a real issue. Since the average person visiting a museum is not an art expert, they don’t necessarily know whether the artist is male or female and only acknowledge what they see. They expect art to speak for itself, instead of being gender identified.

The problem with this mindset is that even if people don’t realise it, being surrounded by the representation of only one minority narrows extremely your exposure to diversity. If we are always, only represented by the same category of people, art will never look like the whole of our culture. Because of this system, there are so many great artists that aren’t even being taken into consideration.

Today, an elite of billionaire collectors and art dealers controls the art world. They’re on museum boards, and pay for what the museum collects. They’re more likely to spend for the same art they already have and that appeals to their values, but we think it should look like the rest of our culture too. In their hands, the history of art turns into the history of power.

For centuries, kings and queens told us what art was about: mostly pictures of them. But now, living in a democratic society, we want art to reflect our collective culture. To be about all of us, and not only white man.

Unfortunately, this is still not a reality.

In 30 years, the issue hasn’t been solved.

I don’t have a solution for this problem, and spreading awareness is all I can do. There’s only one thing I know for sure: we need a change.

Some inspiring women:

- Susan Kare, Iconographer

- What’s Underneath Project

- (I will complete this list, I swear. but right now I have a catalogue to design and no time sorry)

Sources:

- Women in Design lecture slides

- Battersby, C. (1990) Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxBQB2fUl_g&list=LLiLZz7ACIEPbA7WSOvae-CA&index=1

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WqBI20bd2k